Lotus Elite and the LXGT

The story of the Lotus Elite

Later in this article we feature a fine example of the peerlessly beautiful, original-series Lotus Elite, but this one is perhaps the most special variant of the entire production run – the almost legendary ‘big-engined LX’ Chassis No. 1255. But first a little history…

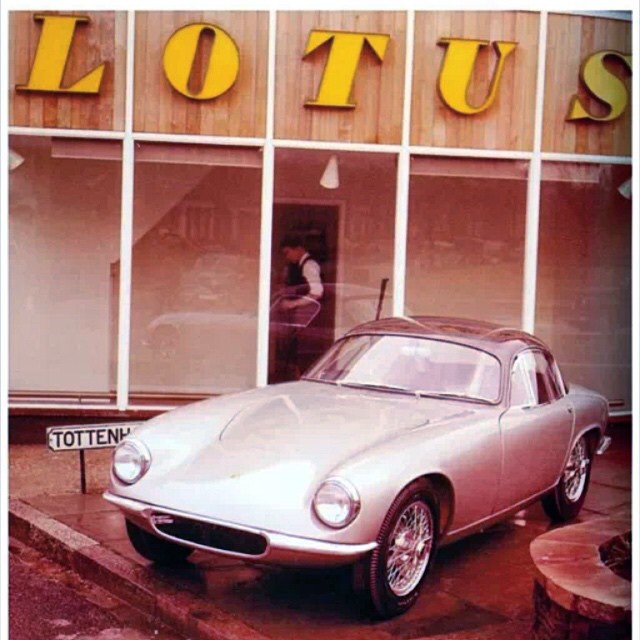

While Colin Chapman was only ever really interested in building racing cars, he was also anxious that his embryo company should have a firm commercial foundation upon which to survive and grow. To provide such a foundation he created the Type 14 Elite as a road-come-racing Grand Touring Coupe, and it was first announced in 1956 as the immensely far-sighted forerunner of a new age of composite-construction, monocoque-chassised performance cars.

Colin Chapman’s Lotus Elite concept – developed in conjunction with his friend, Lotus owner and accountant Peter Kirwan-Taylor- emerged as a moulded glassfibre monocoque chassis/body unit comprising three major mouldings. At the rear a triangular box section provided attachment points for the final drive and rear suspension. The centerline transmission tunnel, sills and roof panel all contributed to the bodyshell’s structural integrity while virtually the only structural-steel item within was a hoop uniting the roof, scuttle and sills. A sheet steel frame provided front suspension pick-ups while a steel section beneath the windscreen supported the steering column, instrument panel and handbrake base.

While its structural concept was breathtakingly futuristic by the standards of the mid-1950s, the finished Elite’s exquisitely proportioned styling is credited to Peter Kirwan-Taylor. Aerodynamicist Frank Costin is said to have advised upon the finished shape, most particularly regarding the cut-off ‘Kamm effect’ tail which contributed to the sleek little coupe’s remarkably low drag coefficient of only 0.29.

While its structural concept was breathtakingly futuristic by the standards of the mid-1950s, the finished Elite’s exquisitely proportioned styling is credited to Peter Kirwan-Taylor. Aerodynamicist Frank Costin is said to have advised upon the finished shape, most particularly regarding the cut-off ‘Kamm effect’ tail which contributed to the sleek little coupe’s remarkably low drag coefficient of only 0.29.

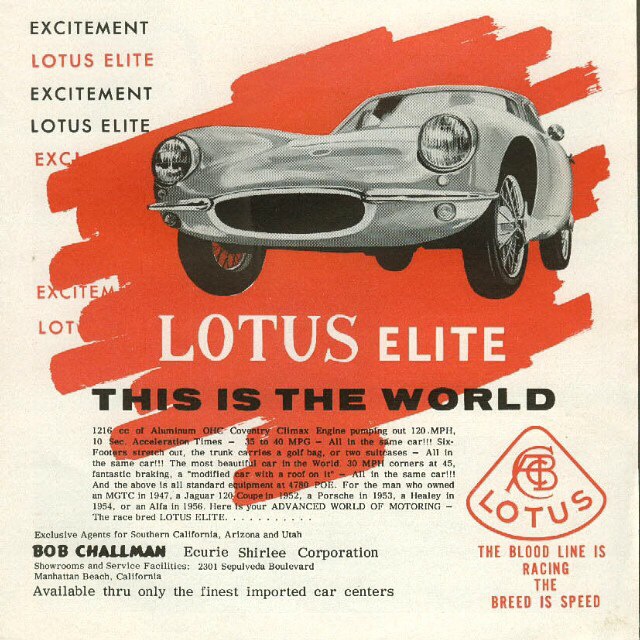

While Colin Chapman was happy that he had achieved highly acceptable standards of accessibility and accommodation with the finished bodyshell, he was disturbed to find so few proprietary engines capable of endowing the finished car with the road-racing performance he also required. Eventually he was able to prevail upon Leonard Lee, head of the Coventry Climax engine company, to enlarge the basic 4-cylinder single overhead-camshaft FWA engine by combining the block and cylinder bore of the FWB with the shorter-stroke of the FWA to displace 1216cc, thus placing the finished car within the up to

1300cc category of International competition.

Power output of this Coventry Climax ‘FWE’ – for ‘Elite’ – engine was a modest 75bhp, but in the sleek and lightweight glassfibre monocoque car it was capable of prodigious race-winning performances within its category. The original intention had been to enter a standard Lotus Elite in the 1957 Le Mans 24-Hour race, but in fact the first running prototype was not available until the Geneva Salon of March, 1958.

Power output of this Coventry Climax ‘FWE’ – for ‘Elite’ – engine was a modest 75bhp, but in the sleek and lightweight glassfibre monocoque car it was capable of prodigious race-winning performances within its category. The original intention had been to enter a standard Lotus Elite in the 1957 Le Mans 24-Hour race, but in fact the first running prototype was not available until the Geneva Salon of March, 1958.

All glassfibre work to produce the original bodyshells was subcontracted by Lotus to external suppliers, the Bristol Aeroplane Company eventually being commissioned to manufacture at the rate of 15-20 per week. Despite Colin Chapman’s reputation-covering protestations that he had only ever intended the new Elite to be a road car, it was inevitable that Lotus aficionados would quickly begin to race them.

Private owner Ian Walker won at Silverstone in the May meeting of 1958 and when the youthful Jim Clark drove one against Colin Chapman in another at Boxing Day Brands Hatch the engineer recognised latent potential in the young Scottish sheep farmer. The 1959 Le Mans 24-Hour race saw Peter Lumsden/Peter Riley finish eighth overall and wining their class – with Jim Clark/Sir John Whitmore 10th in another Elite – while in 1960 a pair of Elites co-driven by Roger Masson/Claude Laurent and John Wagstaff/Tony Marsh placed 1-2 in the 1300cc category and 1-2 in the lucrative Index of Thermal Efficiency competition. In fact Lotus Elites won their class at Le Mans for the following four years.

A Series 2 model was developed with revised rear suspension mounting and improved suspension geometry and at the 1960 London Motor Show an Elite Special Equipment variant was launched with enhanced engine breathing, and some 83bhp. Continuing engine development of the Climax FWE finally saw it offering as much as 105bhp in showroom order. Better headlamps, a heavy-duty battery and even a heater as standard – were also introduced as the ever-beautiful Lotus Elite ran on through its production life into 1963, when it was finally replaced by the more economical-to-produce separate-chassis Lotus Elan.

A Series 2 model was developed with revised rear suspension mounting and improved suspension geometry and at the 1960 London Motor Show an Elite Special Equipment variant was launched with enhanced engine breathing, and some 83bhp. Continuing engine development of the Climax FWE finally saw it offering as much as 105bhp in showroom order. Better headlamps, a heavy-duty battery and even a heater as standard – were also introduced as the ever-beautiful Lotus Elite ran on through its production life into 1963, when it was finally replaced by the more economical-to-produce separate-chassis Lotus Elan.

Today the revolutionary Lotus Elite is rightly revered as an innovative landmark design in the finest Lotus tradition, immensely desirable, and an asset to the collection of any true Grand Touring car connoisseur.

The ex-works 1960 Le Mans 24-Hour race 2-litre Lotus LX GT

The cars made their mark in competition from 1959 forward and in 1960 this very special version of the futuristic little Coupe was built with one major objective in view. It might, with luck, just have been capable of winning the Le Mans 24-Hours race, the most prestigious single-race prize in the world of international motor sport.

The engine to be used was a 2-litre Coventry Climax FPF twin-overhead camshaft unit, a very different proposition from the specially-tailored 1216cc Climax FEW 4-cylinder single-cam unit with which standard production Elites were equipped.

The engine to be used was a 2-litre Coventry Climax FPF twin-overhead camshaft unit, a very different proposition from the specially-tailored 1216cc Climax FEW 4-cylinder single-cam unit with which standard production Elites were equipped.

The new car possessed immense promise as it combined a huge boost in both power and torque with its tiny frontal area, slippery shape and ultra-lightweight construction. However, its Le Mans foray was ill-fated from the beginning. It had been entered by Lotus Engineering and had been jointly financed by enthusiastic amateur owner-drivers Jonathan Sieff – scion of the Marks & Spencer retail family – and Michael Taylor.

The latter had been a prime customer for the first Formula 1 Lotus-Climax 18 single-seater which he entered in the 1960 Belgian GP, only to suffer a life-threatening crash during practice when the car’s steering failed, pitching him way off circuit at La Carriere corner, ending up deep in the forest, grievously injured and in fact overlooked as rescuers attended to Stirling Moss, injured when his 18 had crashed on the opposite side of the long circuit.

Next day, the Belgian GP proved even more tragic for Team Lotus as long-time loyal driver Alan Stacey was struck in the face by a bird, lost control of his Type 18 and died in the ensuing crash near Malmedy. Alan Stacey had been entered to co-drive the new LX at Le Mans, sharing the wheel with Innes Ireland. Alan Stacey had been motor racing mentor to a fellow Essex-based enthusiast, the youthful Sir John Whitmore. He was at Le Mans as a reserve driver with the Aston Martin team, but as news of Stacey’s death was digested he was released by Aston to share the Lotus LX with Innes Ireland.

However, he found the normally rugged, but always temperamental and demonstrative, Scot was even more deeply affected and depressed by Stacey’s death than he himself. Innes had completed just one practice lap in the new car before its 2-litre engine began to overheat. Innes also considered that the car was too softly suspended and nose heavy – although its scrutineering weights (712kg overall – distributed 318kg front/394kg rear) indicated that if anything it was actually tail-heavy. Post-practice it was found that one rear tyre was under-pressure, but Innes Ireland’s confidence had been sorely tested and proved wanting.

However, he found the normally rugged, but always temperamental and demonstrative, Scot was even more deeply affected and depressed by Stacey’s death than he himself. Innes had completed just one practice lap in the new car before its 2-litre engine began to overheat. Innes also considered that the car was too softly suspended and nose heavy – although its scrutineering weights (712kg overall – distributed 318kg front/394kg rear) indicated that if anything it was actually tail-heavy. Post-practice it was found that one rear tyre was under-pressure, but Innes Ireland’s confidence had been sorely tested and proved wanting.

Later, when Sir John drove the car with its tyres properly pressured he was impressed by its potential – but his enthusiasm could not raise the cloud which had settled over the Lotus Le Mans team… and it then grew even darker.

Jonathan Sieff was practicing in his own 1216cc Lotus Elite when the car left the road at very high speed on the Mulsanne Straight and sliced in two against a trackside electricity pylon. The driver was very badly injured and while he lay in jeopardy in an intensive-care hospital bed, Innes Ireland abruptly decided he wanted no part of Le Mans that year. He borrowed Sir John Whitmore’s minivan – bought because they were free of purchase tax in the UK and provided standard Mini performance and cornering for just £395 – and set off for the ferry home. Without a co-driver the Lotus LX entry at Le Mans had to be cancelled and the car that Colin Chapman really considered a true challenger for major success there would not start the Grand Prix d’Endurance.

This is a car that could prove devastatingly quick in a wide range of historic events. From a serious collector’s point of view, it would be attractive as the interesting oddball that never raced as its designer intended but, to a competitive driver, it must look like a secret weapon that has been hidden away for too long. – Tony Dron in ‘Octane’ magazine after testing the LX at Goodwood.

In a typically last-minute Lotus frenzy, the LX was completed in a rush for Le Mans, but great thought was invested in its preparation. Its engine bay was reinforced to accommodate the torque and power of the enlarged engine while the gearbox and final-drive were also specified to match… for 24 hours. Fuel capacity was increased markedly, with a 12.8 gallon tail tank augmented by an additional 9 gallon tank shoehorned into the nearside front wing section. Overall fuel capacity was 21.8 imperial gallons.

In a typically last-minute Lotus frenzy, the LX was completed in a rush for Le Mans, but great thought was invested in its preparation. Its engine bay was reinforced to accommodate the torque and power of the enlarged engine while the gearbox and final-drive were also specified to match… for 24 hours. Fuel capacity was increased markedly, with a 12.8 gallon tail tank augmented by an additional 9 gallon tank shoehorned into the nearside front wing section. Overall fuel capacity was 21.8 imperial gallons.

Suspension, brakes and steering were all derived from the parallel Lotus 18 Formula 1 program, but the LX was externally almost indistinguishable from the standard production cars – just two bonnet top NACA ducts and larger-than-standard 5.00×15 front and 6.00×15 rear wheels giving away the 2-litre FPF-engined game.

The car was sold later that year to the independent Team Elite organisation, with the objective of running at Le Mans in the 1961 24-Hours but even that plan was then pre-empted when the LX was crashed in a club race at Rufforth airfield in April, 1961, and then Team Elite encountered financial difficulty. The damaged LX was dismantled and the bodyshell was rebuilt to accommodate the normal Climax FWE engine as a club racer.

The now 1216cc re-assembled racer would be formally road-registered in the UK and, starting with a new owner named W.A. Bickerton-Jones, the car passed through five different ownerships. Its sixth owner, seeking to establish the true story of his newly-acquired Lotus Elite, approached Ron Hickman – millionaire engineering mastermind behind the Workmate concept who in period had been Lotus’s chief road car designer.

After some days of painstaking examination, Mr Hickman confirmed “with 100% certainty” that the bodyshell is that of the original Le Mans 2.0-litre Elite.

A complete ground-up restoration to its original specification was then undertaken by leading specialist Kelvin Jones, representing a six-figure Sterling investment. The re-completed car with 1964cc twin-cam Climax FPF engine, developing some 176bhp at 6,500rpm, has been track-tested satisfactorily on three different circuits. It is self-evidently today a 2-litre Grand Touring car of prodigiously competitive historic racing potential.